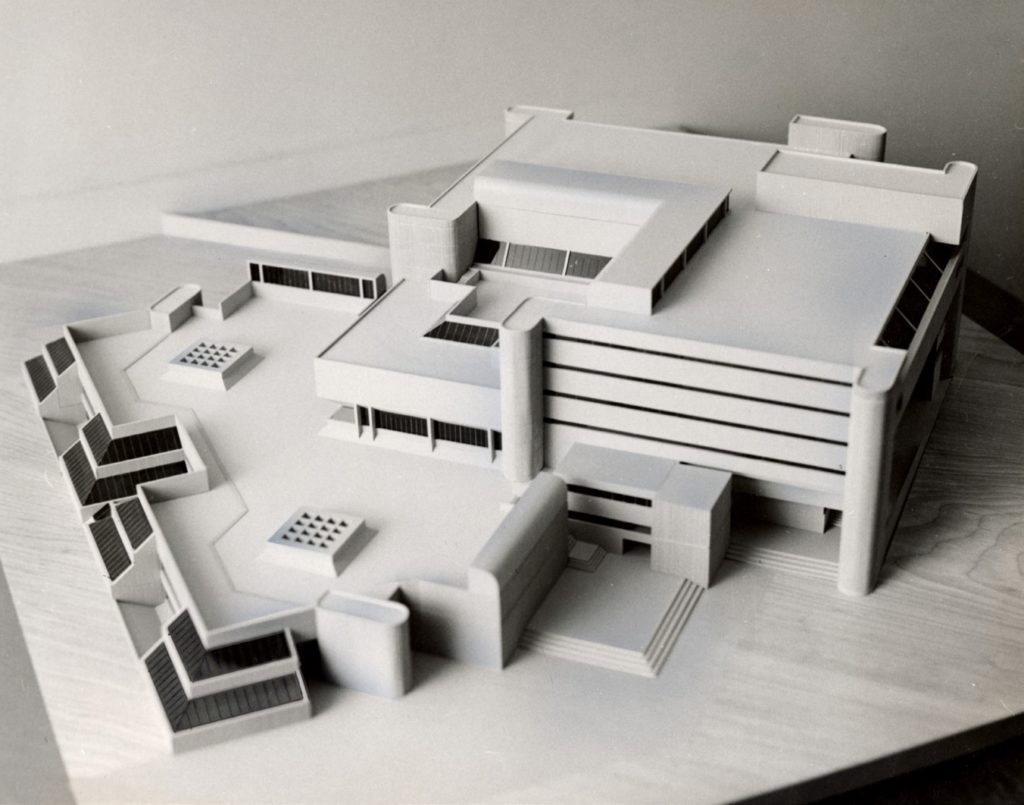

THE ARCHITECTURAL MODEL ILLUSTRATES THE STEPPED FORM, AXIAL PLAN, DIAGONAL GEOMETRY, COLUMNAR CORNER TOWERS, AND SKYLIGHTS OF THE “NEW MAIN LIBRARY” (RONALD E. MURPHY ARCHITECT AND JOHN ANDREWS ARCHITECTS, C. 1967), UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO, LONDON. | AFC 399-7, WESTERN ARCHIVES, WESTERN UNIVERSITY.

What comes to mind when you read the word Brutalism? Is it massive structures with strong geometric angles? Maybe you picture minimalist buildings that feature raw concrete and exposed pipes and conduits? On the whole, Brutalism is an architectural style that invokes many a feeling – and it’s the style at the heart of Weldon Library.

Brutalism: A Very Brief Overview

Brutalism emerged out of the post-war reconstruction of the 1950s. Steeped in the modernist tradition of architecture, and the underlying principle that form follows function, Brutalism sought a reclamation of public space. Contrary to the popular belief that the style is defined by its materiality, primarily the use of raw concrete (or béton brut), Brutalism is rooted in a much richer architectural ethic.

Oli Mould (2017), for example, argues that the Brutalist tradition was guided by three fundamental values: to celebrate “…the power of the image, [the] clear and transparent exhibition of structure and the value of the materials ‘as found'” (p. 704). In other words, Brutalism wanted to peel away a building’s ornate and lavish finishings emblematic of the time to reveal and celebrate its structural core. While this may read like architectural rhetoric, the underlying goal was simple: create spaces that could be inhabited by everyone, without the fanfare. While this ethic can be applied to many public buildings, it perhaps especially well-suited to libraries. Rooted in the notion of intellectual freedom and diversity of thought, libraries embrace difference, and the beauty therein.

Brutalism and Weldon Library

Built between 1968 and 1972, Weldon Library represented a marked departure to the gothic architecture on campus. Architects Murphy and Andrews were chosen for the project and settled on a megastructure design rooted firmly in Brutalism. The decision to deviate from gothic design was certainly experimental but it also served a symbolic function: to establish the library as the heart or ‘hub’ of campus (James, 2019). Furthermore, a design was chosen that focused on the experience of the individual, with an eye towards human interaction.

Consider the original design of Weldon and the emphasis on the shared spaces of the ground and main floors. Visitors entered the library via a narrow tunnel that spills out into a large open area midway between the two levels. The main floor was the destination for visitors, with library reference, circulation, and the card catalogue, while the ground floor allowed for a more relaxed and quiet work environment. In both cases, the architecture was used to compliment a sense of belonging and shared use of space.

Another interesting element of Weldon’s design was the explicit consideration for future expansion. Having found the ideal location, librarians and leadership wanted to be sure that they could expand as necessary. Murphy and Andrews included this in their plans and came up with a design that would allow for expansion in a phased approach. Each addition to the building would occur radially, culminating in a large orthogonal structure with three pentagonal lobes (James, 2019). While future expansion didn’t happen exactly as envisioned, Murphy and Andrews plans remain visionary.

Weldon has seen several space changes over the years and it’s about to enter yet another phase of design. Like previous iterations, though, current renovation work on this library not only preserves but embraces the Brutalist legacy of celebrating structure through a distinctly humanistic lens. It’s our utmost goal to respect Weldon’s architectural history and style, while we open up new, more intuitive routes through the building, putting the learning environments, services, and resources of the library on display.

References

Ashby, J. (2019). The D.B. Weldon Library by Andrews and Murphy: Modern Experiments in a Collegiate Gothic Campus. Journal of the Society for the Study of Architecture in Canada, 44(2), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.7202/1069482ar

Mould, O. (2017). Brutalism Redux: Relational Monumentality and the Urban Politics of Brutalist Architecture: Brutalism Redux. Antipode, 49(3), 701–720. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12306